Black Femme Queen Theology: Prophetic Worship as Community Practice

By Minister-in-Training Nala Toussaint

Black Femme Queen Theology: Living Archive Series

Prophetic Worship

Prophetic worship is not just about songs or sermons; it’s about truth. It’s about worship that refuses to disconnect from justice, that calls out systems of harm, and that breathes life into communities who are told daily that we should not exist. Prophetic worship is where ritual meets resistance, where praise becomes protest, and where Spirit shows up in the streets, in the ballroom, on the runway, and in our everyday survival.

What Prophetic Worship Is

When theologians describe prophetic worship, they say it’s the kind that unsettles and shakes foundations (Labberton 2012; Brueggemann 2001). But for those of us living on the underside of empire, prophetic worship is not theory; it’s lived reality. It’s showing up in the spaces where we’ve been told we don’t belong and turning them into holy ground. It’s survival infused with Spirit. It’s glitter and gospel woven into one body.

For me, prophetic worship is a merging of two truths: God’s call for justice and the resilience of marginalized communities. It is both biblical and biographical. It’s rooted in the ancient cry of prophets like Amos, who said, “Let justice roll down like waters, and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream.” And it’s rooted in the everyday lives of those of us who have been exiled, yet refuse to give up our praise. Prophetic worship is embodied; it’s our bodies declaring, without apology, that we are temples of the living God (Junker 2021).

Jasmine Bonet: An Embodied Sermon

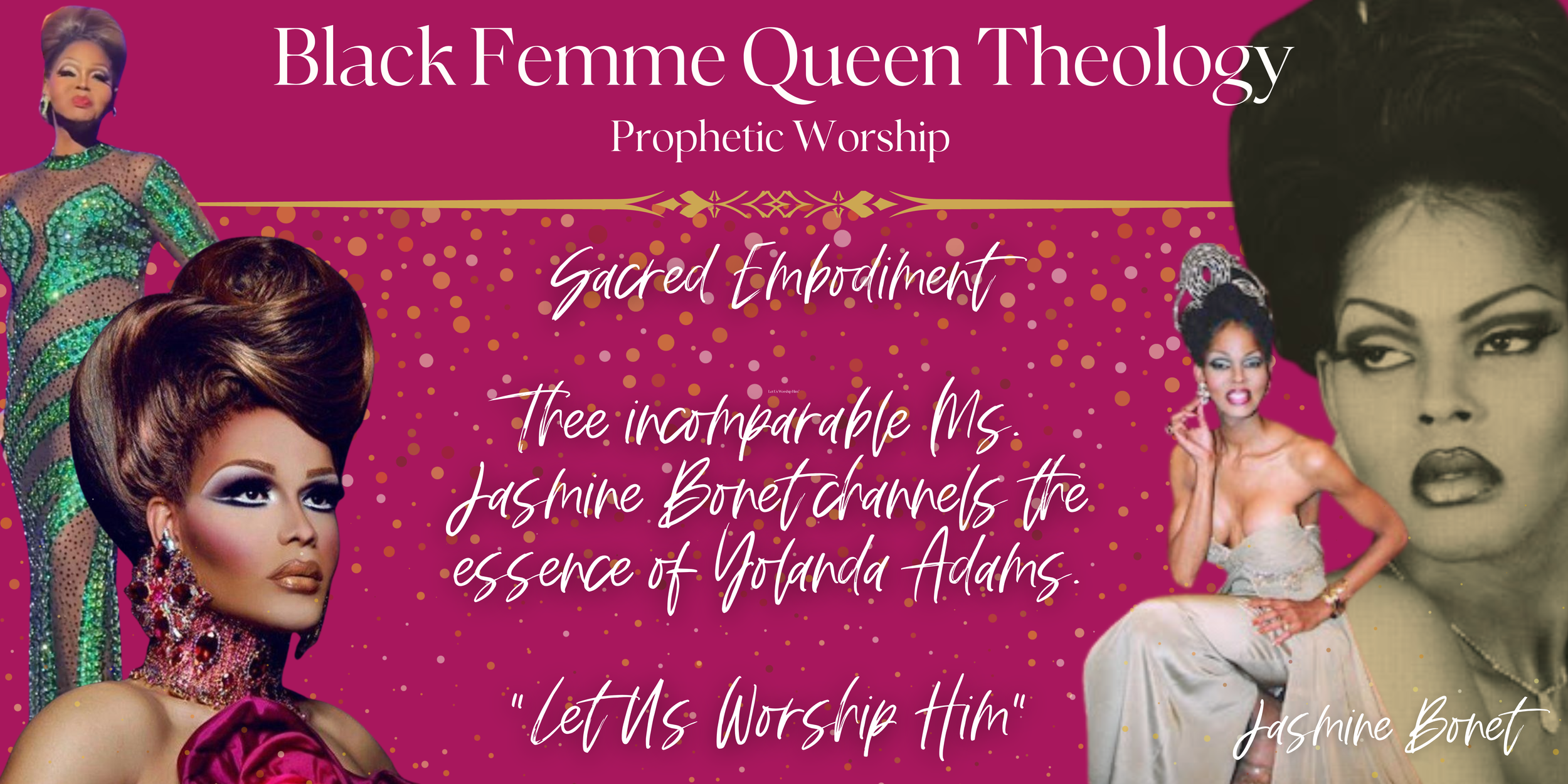

The 2009 performance of Jasmine Bonet at Virginia Icon Continental is one of those moments that cannot be dismissed. Pantomiming Yolanda Adams’ “Let Us Worship Him,” Jasmine preached without speaking. Every gesture was prayer, every step was prophecy. In that moment, the stage was a pulpit. Her body became scripture. What others might call entertainment, we recognize as liturgy. What others might dismiss as performance, we understand as testimony.

To expand on Jasmine’s offering, it’s important to understand who she was and what she represented for so many of us. Jasmine Bonet, known as Thee Incomparable, was a legendary entertainer and pageant queen whose artistry embodied a depth that was spiritual as much as it was glamorous. She carried herself with grace and authority, moving audiences not only with her skill but with her capacity to translate Spirit into movement. Her 2009 performance was not simply an act; it was a proclamation. By lip-syncing to Yolanda Adams, she bridged the world of gospel music with the world of pageantry, declaring that holiness can be found in spaces the church often condemns.

Jasmine’s performance invited people into worship who may have long felt exiled from sanctuaries. For queer and trans audiences, especially Black and Brown LGBTQ+ folks raised in faith traditions, seeing Jasmine take the stage and embody the song was a revelation: worship could look like us. It affirmed that the Spirit does not require institutional permission to show up. God was moving through Jasmine’s body, through her sequins and gestures, through her breath and timing. She was preaching a sermon without ever holding a microphone.

Jasmine Bonet’s resemblance to Janet Jackson was more than aesthetic; it was symbolic. She brought the essence of celebrity to communities of Black and Brown trans and queer folks who were often struggling, poor, and dismissed by the world. In her presence, people were given a glimpse of glamour, a taste of possibility, and a reminder that they were worthy of being loved, heard, and seen. Jasmine’s beauty and presence carried with them a ministry of affirmation. She reminded us that holiness could arrive adorned in sequins and that God’s love could be reflected in the glow of her presence. For many, her ministry was not only in the choreography but in the way she made us feel considered, worthy, and radiant.

Her legacy reminds us that prophetic worship can live in unexpected places. The ballroom floor can become an altar. A stage can become a sanctuary. A queen’s body can become the vessel of God’s truth. Jasmine’s artistry was not only survival; it was ministry. Her embodiment challenged the limits of who gets to speak for God and whose bodies are recognized as sacred (Bailey 2013; Moore 2020). And her role in pageant systems like Miss Black Universe (MBU), founded to provide Black LGBTQ+ communities with their own platform of excellence, underscores how Black pageantry has long functioned as a sanctuary of truth and artistry (Roberts 2007).

Why This Matters

Prophetic worship matters because it tells us something about who God is and who we are. For the world, prophetic worship serves as a reminder that faith cannot be limited to rituals disconnected from justice. It challenges empty ceremonies, hollow prayers, and traditions that ignore suffering. It demands that worship be tied to transformation; transforming systems, communities, and lives (Williams 1993; Cannon 1995).

For our people, prophetic worship is a life-saving experience. In a world where Black trans femmes are constantly facing violence, stigma, and exclusion, prophetic worship declares: we are holy. It says our joy is sacred, our gatherings are survival, and our very breath is resistance. It crowns the rejected, and it refuses the lie that God cannot dwell in us. Prophetic worship expands the story of holiness, insisting that God is not only in stained glass windows but also in sequins, in movement, in our survival (Snorton 2017; Ellison and Douglas 2010).

This matters for the masses because prophetic worship is not locked away in seminaries or pulpits; it belongs to everyone. It invites all people to see their lives as sacred ground. It calls for justice not just in church buildings but in schools, hospitals, courtrooms, prisons, and neighborhoods. It reminds us that if worship doesn’t lead us to love more deeply and fight more boldly, then it is not prophetic.

Black Femme Queen Theology as Lived Experience

When I talk about Black Femme Queen Theology, I’m not offering an abstract idea. I’m naming what is already alive in our communities. This theology is born from study, yes, but more importantly from survival, sequins, laughter, tears, and resilience. It’s rooted in my own life as a Black trans femme and in the lives of my sisters and siblings who have carried both grief and glory in our bodies.

Black Femme Queen Theology says our existence is worship. Our adornment is testimony. Our joy is a form of prophecy. We don’t separate worship from life because our very lives; our walks, our dances, our prayers, our survival; are worship. This theology reclaims the power to lead, to preach, and to prophesy with the same bodies the world has tried to erase.

A Call to Our Community

To my siblings, elders, and beloveds: prophetic worship is ours. It’s not reserved for pulpits or choirs. It’s in our kitchens, where food becomes communion. It’s in our ballrooms, where every spin and dip is holy. It’s in our vigils, where our tears are psalms. It’s in our family reunions, where laughter becomes prayer. It’s in every moment we gather and proclaim with our bodies, God is with us. We are holy.

Prophetic worship is truth-telling, justice-making, and life-affirming. It’s what crowns us, holds us, and carries us forward. It is the heartbeat of Black Femme Queen Theology, reminding us that we are the living testimony of God’s glory.

References

Bailey, Marlon M. Butch Queens Up in Pumps: Gender, Performance, and Ballroom Culture in Detroit. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2013.

Brueggemann, Walter. The Prophetic Imagination. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2001.

Cannon, Katie G. Katie’s Canon: Womanism and the Soul of the Black Community. New York: Continuum, 1995.

Ellison, Marvin K., and Kelly Brown Douglas, eds. Sexuality and the Sacred: Sources for Theological Reflection. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2010.

Junker, Donna. The Prophetic Imagination and the Practice of Ministry. Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2021.

Labberton, Mark. The Dangerous Act of Worship: Living God’s Call to Justice. Downers Grove, IL: IVP Books, 2012.

Moore, Paris. “The Sacred and the Ballroom: Queer Performance as Spiritual Resistance.” Journal of Black Sexuality and Relationships 7, no. 2 (2020): 35–54.

Roberts, Monica. “A Pageant of Our Own: The MBU Pageantry System.” TransGriot, January 17, 2007. https://transgriot.blogspot.com/2007/01/pageant-of-our-own-mbu-pageantry-system.html.

Snorton, C. Riley. Black on Both Sides: A Racial History of Trans Identity. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017.

Williams, Delores S. Sisters in the Wilderness: The Challenge of Womanist God-Talk. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1993.